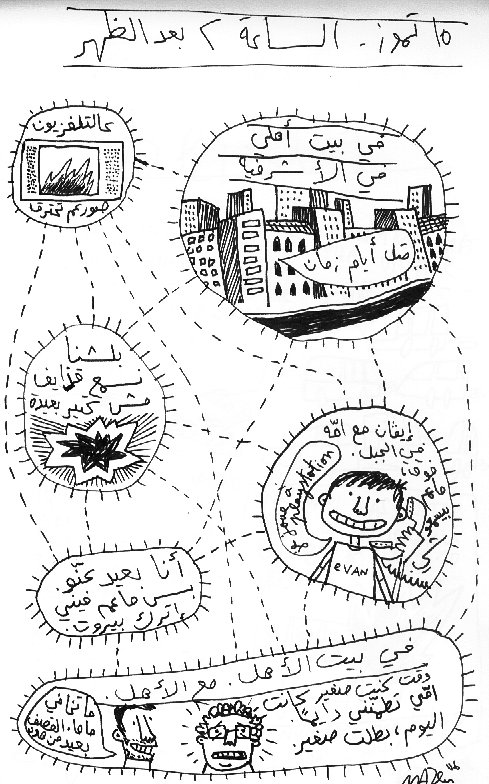

(image by Mazen Kerbaj, from his blog )

(image by Mazen Kerbaj, from his blog )I am such a slacker when it comes to writing. It always seems to difficult to finish things. There are so many ideas and interesting questions popping up once in a while, yet I never get to write them down. I'm living in a state of a life-long writer's block, I fear. As you could see, I have quite negelected my Moers Festival reviews in the past days. And today another idea had formed, the idea for an essay about a) music in times of war and b) whether the context of a musical performance is part of the music. The latter question was formed (again) yesterday, when I listened (again) to a recording of Wilhelm Furtwängler conducting the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra in 1942. They were playing Beethoven's 9th symphony. A piece that has been performed a thousand times before and a million times afterwards. So, nothing special. But wait. 1942? Berlin? At that time that was the headquarter of evil. At that time German evil was bringing a desastrous violent inhuman bloodshed over the world. And at that time a man named Furtwängler, who has been instrumentalized by the Nazis to show the world what a high-class cultural life there exists in Germany, makes a choir sing joyously: "Alle Menschen werden Brüder" ("All men become brothers"). What is that? Starry-eyed idealism, chuzpe, misunderstanding of facts, insanity, an act of resistance? It's hard to say without doing a very deep survey on that matter. Yet maybe the even more interesting question is: Is the Nazi- and wartime context an inseparable part of this performance? Can we understand the performance without considering the Second World War? Or is the contrary true: Do we have to try neglecting the circumstances and concentrate on the "absoluteness" of the music itself? The question not only arises in the 4th movement where the choir sings lyrics that are in stark contrast to Nazi ideology, but already in the instrumental movement before. The first movement seemed not to conflict with the Nazis and the wartime, as it was played rather muscularly, in a swashbuckling way. The second movement didn't make much impression on me. But then, the third movement is not just played in a very beautiful and tender way, but also in a way that seems to depict a free exchange of human spirits. So I feel the starkness of the 4th movement is already prepared in here, in a purely instrumental way. By the third movement we could say, the performance turns into an anti-Nazi demonstration, probably right under the eyes and ears of the Nazis who were sitting in the audience.

I remember the French professor and writer Adrien Finck has written a short essay about this performance ("Musica in Extremis"), published in the Révue Alsacienne de littérature 84 in 2003. I've got to find this again and re-read it to see if Finck can help me answer my questions.

And then, I've got to think on, about what options musicians do have if they live in a country ravaged by war. I remember Mazen Kerbaj's recording of a trumpet improvisation, played and recorded on his balcony in Beirut while Israeli bombs were dropping onto the town. There's no question about it: the context in general and the war in specific are part of the musical performance here. Yet is it so different from Furtwängler? Isn't the music in both cases competing with the war, isn't it fighting the war with its own means, only seemingly week, but infusing us with sparks of hope?

I would like to write an essay about the questions raised here, yet I fear I never will. I am such a slacker.

7 comments:

It's certainly a topic that could make a very interesting essay. Of course, during times of crisis (real or manufactured), music serves powerful propaganda purposes which, in some cases, seem to directly contradict the music itself. So, for example, American jazz being used as a 'weapon' in the Cold War, an expression of the 'freedom' of the United States, when at the same time these African-American musicians had to live in a country and culture that was still marred by a deep-set, ingrained and often institutional racism. What about war songs? Music perhaps plays a less important role in the actual physical fighting of wars than it used to - no armies marching into battle with pipes and drums - but we might think of contemporary examples such as the US military listening to aggressive rock music as part of the process, conscious or not, of dehumanising the enemy. Or the use of music, played at ear-splitting volume, as torture in Guantanamo Bay. (Which might raise disturbing questions for practioners of noise music - the closeness of what they do to practices of sonic torture). I hope you manage to return to these thoughts at some stage!

I'd say the Kerbaj track is very different, since it is about the individual and a right to exist in the face of a warfare that aims to become more and more abstract.

I'd also say that you cannot separate a Furtwängler interpretation from his thought that musical genius is superior to the circumstances of all the crimes that may be committed all around, so there's no easy way out, these are clearly political interpretations, done from within a system that supported them.

David and Lutz, thanks for your comments, thanks for raising further questions. I fear, the more questions we raise, the less easy it will be to find answers. Nevertheless, it's all worth consideration: Noise music and torture (so is loving noise music self-torturing, are noise lovers masochists?), re-listening to the wonderful Trikont compilation "Hitler & Hell - American Warsongs" in relation to the racial and social position of the musicians presented there, and as Lutz indicated, in the case of Furtwängler we'd have to take into account the idea of the "autonomy of the arts" as it was clarified by the considerations of Adorno. Well, that rather looks like the plan for a book rather than for an essay... Sometimes I curse my associative thinking...

... and I've finally added an Eartrip link to my blogroll. What a shame I hadn't done so earlier. Sorry, David.

hmm, you are just too busy. I don't like to be busy, you know that. So I feel painful either when my thought is in status of fragments, or when there are too many things stuff in my mind, just like when one would have to live in the constant noise. hehe

Keep going.

Audrey Rocigli, 'Le cas Furtwangler', Imago, Paris 2009 is rather good on this matter...

Merci pour l'information. Ce semble très interessant. Alors je l'ai déjà commandé. Etes-vous l'autrice elle-meme, ou avez-vous seulement les memes initiales?

Post a Comment